It was that Monday again. Shifting a plate of half-eaten toast to the edge of the kitchen table, Zoë checked her list and started making calls.

They answered on the seventh ring.

“Hello, Travelodge Telford.”

“Hello,” said Zoë, slipping into the ‘work voice’ her housemates always teased her over. “I’m calling to inquire abo—”

“That time again is it?” the receptionist cut her off, in a voice that was neither cruel nor particularly cheerful.

“Time is absolutely flying,” said Zoë.

“Right,” he replied. “Well, we have a room tomorrow. One night with breakfast, £35.15. Do you want me to book that for you?”

“No,” said Zoë. “Of course I don’t.”

Swift justice

We made Zoë up. But her story could be true.

Every month, during the Monday of “index week”, agents of the Office for National Statistics like our fictional heroine are tasked with collecting a range of hotel prices.

Over the internet or via old-fashioned phone calls, they trawl hotels to discover the cost of one night in room with breakfast for Tuesday. The prices they observe will form a small part of the inflation basket, which will mostly be filled over that next day.

In the latest consumer price index figures, this “Hotel 1 Night Price” item was weighted at about 0.3 per cent of the overall basket — higher than water and wine, but behind vodka and pub meals.

Usually, it isn’t a big deal, but that changed last summer, around the same time a global obsession with pop star Taylor Swift led to the ‘Me!’ singer suddenly being credited with just about everything happening in the economy:

FT Alphaville wrote a couple of times last summer about how a jump in ONS-imputed hotel prices during June was likely not the work of Miss Americana.

Our crucial point, insofar as we had a point, was that even if Swift’s appearances did lead to hotel price gouging, that gouging would not have matter from a national statistics perspective unless her appearances coincided with ONS price collection days. Which they didn’t:

So if the ONS was missing Swift, what were they capturing? Well, as it turns out, there a large number of other musical acts who are also popular.

Missundaztood

Alecia Moore-Hart is probably not a household name in the UK, but her stage name, Pink (often styled as P!nk), certainly is.

The “Just Like A Pill” singer’s Summer Carnival tour ran for 97 shows, from summer 2023 to autumn of last year. According to Billboard, it was the second-highest-grossing tour by a female artist ever, landing ahead of Beyoncé’s Renaissance, and behind — you guessed it — Swift’s Eras.

Among a number of appearances across the British Isles, she appeared at Cardiff’s Principality Stadium on 11 June, bulls-eyeing the price collection day for that month:

If a hotel in Cardiff increased its prices on the night of the 11th in response to high demand linked to Pink’s appearance, there’s a possibility that could then feed into the UK’s inflation data.

Now, we can’t see specific figures for Cardiff, but the ONS’s price quote tables do show agents’ attempted observations for Wales as a whole. How many hotels did they canvass that June?

Four. Four hotels across Wales, a country of around 3 million people and home to, uh, the ONS.

Of those four hotels, two produced a price: one of £57 for the night, and one of £369. The other two got a T indicator, for “Temporarily out of stock” — in other words, the hotel was fully booked.

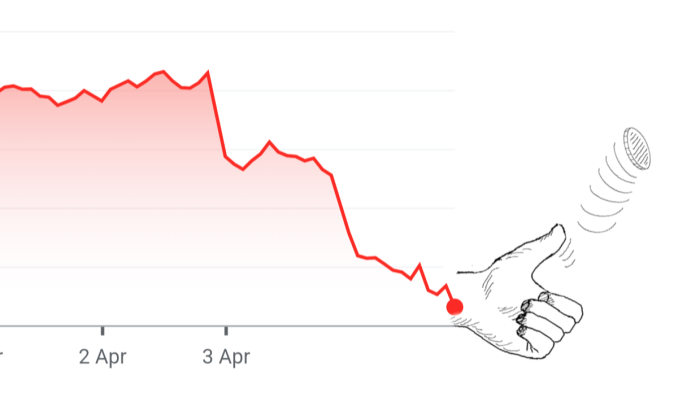

The £57 room’s price was flat on the previous reading, while the £369 room’s price had almost tripled:

You probably don’t have to be a sell-side economist to work out why that chart is bad. As of last June, Welsh hotels represented 5.67 per cent of the “Hotel 1 Night” item. Alongside some other individual surges in the South West and East Anglia, this hotel was probably a major driver of inflation in broader category.

This Pinkcident was brought to our attention Rob Wood from Pantheon Macroeconomics, who noticed it at the time and mentioned it to us while we were nagging him about video games last week.

It’s a clear example of how easily Hotel 1 Night Stay can be skewed, and then how that potentially feeds up to headline numbers.

The ‘no room at the inn’ issue

Like many works of fiction, our short story at the top of this article included an improbable event: Zoë managed to find a room.

It’s probably a little tricky to eyeball this from the chart above, so let’s specifically look at the number of valid Welsh hotel price quotes the ONS’s agents have been able to get each month since 2019. It’s, uh, horrible:

So, out of the seven hotels it has tried to get prices from since September 2019, the ONS have never successfully extracted a valid price from more than four.

Even if we ignore the lockdown-era disruption, the change in price has frequently been derived from a single hotel price, or none at all — as was the case in the most recent figures.

It doesn’t much imagine to guess why this might be happening: if you try to book a hotel room the day before you plan to arrive, you’re often going to find that they’re full. You’re also going to end up in a weird valley regarding dynamic pricing: sometimes, you’re begging for a gouging, while other times the hotel might be desperate to fill a room.

And it’s not just a problem in Wales:

And unlike with video games, there’s no major apparent shift in the style or amount of gathering going on here:

An ONS spokesperson told us:

The observation for the traditional overnight hotel accommodation is as described. The price is collected on the Monday of collection week for an overnight stay the following day. This can mean that some accommodation is fully booked and prices can be affected by short-term demand.

So what?

It isn’t good for the stats beneath the stats to be this bad. And unlike with an innocent small caged mammal, hotels are significant enough to sometimes matter a bit to overall CPI.

Not all items are alike. But, as we observed long ago, price collection rates (successful or not) are radically different for different items. Under ideal circumstances, you’d hope that the more important the item to overall, the more the ONS is trying to measure it.

Lol, nope:

Much to consider.

So what’s the solution? We already know the ONS is slowly attempting to make tweaks, most significantly by mass price gathering from sources like supermarket scanners.

Hotels don’t seem to be getting the big data treatment just yet, but, happily, a fix of sorts is in: we’d like to be among the first to congratulate the ONS on its new inflation spawn, HOTEL ADVANCE PRICE 1 NIGHT. We don’t appear to have price quotes for this beautiful new baby in a basket, added in February, but hope to see some soon.

An ONS spokesperson told us:

As part of the latest basket update, we have added an extra item to cover overnight hotel accommodation booked further in advance. This will result in additional quotes and should reduce the volatility in the series, aiding interpretation. We are also retaining the existing item so that late-booked accommodation is represented.

Huzzah! Still, our national statistics are going to occasionally going to be victim to strange circumstances. And we’re happy to give Pink long-overdue props for her part in that.

Further reading:

— The ONS vs the Xbox