Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Retail & Consumer industry myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

American households are about to take a wild ride through the basics of global economic policy, thanks to their country’s Big Beautiful Leap Forward. Or the Great Leap Onshoreward, if you’d prefer.

This is being signaled very clearly by Thursday’s stock-market moves. Are stocks the economy? No. But they have direct effects on the capital costs of companies, who are the economy (especially during an ongoing project to strip the public sector of power). And stocks can provide a pretty good outlook of what investors expect.

Today, at least, investors see a big reckoning for the American consumer. For a while now, the American Pitch has been that if you sacrifice universal healthcare, you can buy cheap screens and nice clothes, and maybe dream of becoming very wealthy and powerful despite your worsening statistical chances. This deal used to involve homeownership, but that was ages ago (before 2008).

Now the White House’s narrow focus on bilateral trade balances threatens to end the rest of the Cheap Stuff party.

That will probably have broader economic implications. But first, let’s step back and look at the shares of companies that sell Stuff.

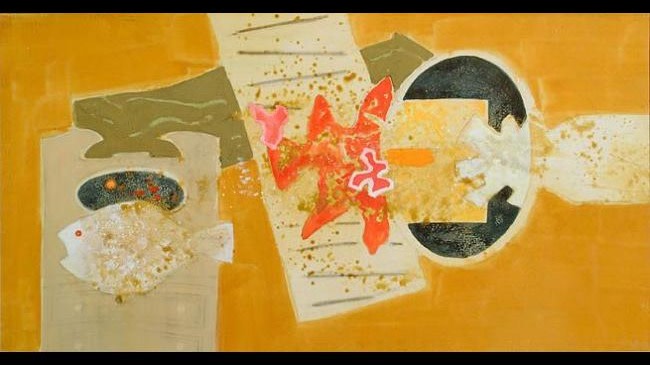

They’re tanking, predictably, because countries like Bangladesh, Cambodia, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Vietnam all face the biggest “reciprocal” tariff burdens, and are big exporters of consumer goods like textiles and electronic parts. We’ll call these the American Stuff Stocks:

As you can see above, the S&P 500’s biggest losers today include retailers like Ralph Lauren, the mega-Americana brand, and Deckers Outdoor, the maker of Uggs. About 35 per cent of RL’s suppliers are in China and Vietnam, which got hit with tariffs of 34 per cent (on top of the existing ones) and 46 per cent, respectively.

Toymaker Hasbro and electronics retailer Best Buy are both down bad too. Same goes for Williams-Sonoma, which sells higher-end home goods.

Home-goods store RH (fka Restoration Hardware) has fared even worse on Thursday. As its CEO said in the company’s earnings call today, with our emphasis:

I mean, I guess, the stock went down based on some of the numbers we reported and then it got killed because of a – oh, really? Oh, shit, OK.

Sure, you could argue that all of this will be offset by substitution effects and domestic investment within the US.

But the Secondary Stuff Stocks, whose profits rely more on consumer spending than tariffs, aren’t looking so hot either:

Synchrony Financial isn’t an importer! It does, however, sponsor the retailers’ store cards that shoppers use to sign up for discounts. So it’s down bigly as well. Airline and cruise stocks, which are also tied to consumer demand, are also falling (their capital spending is big, but rarer and often financed separately).

This trade pretty clearly goes beyond the mechanical tariff impacts, though. Gambling stocks are selling off hard, and they don’t really sell Stuff! But people do gamble less if they don’t have money to spend. Ideally.

And then we have the Staple Stuff stocks:

On the other side of the vice ledger from gambling, shares of cigarette maker Philip Morris are doing just fine.

Investors also appear to be more bullish on soup (Campbell Co) and processed grains (General Mills). No need to worry about GMO grains or Red-40 if you can only afford to have cereal for dinner!

The best performer in the consumer staples sector? That’s Lamb Weston, which sells frozen potatoes.

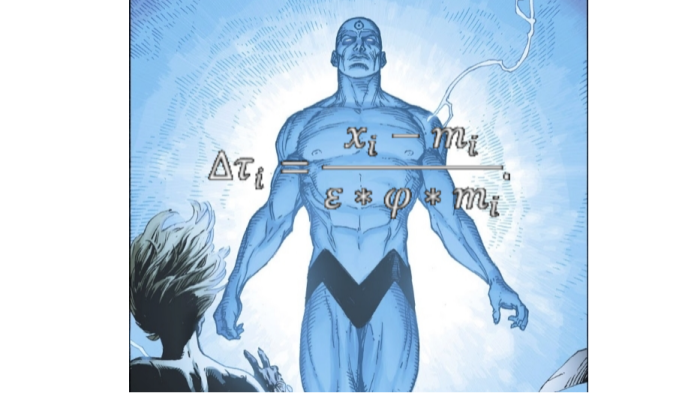

And this is all before we even get into the rates market, which is sounding the siren of recession. The US yield curve is now inverted as Hell, to use the technical term.

As Unhedged’s Rob Armstrong pointed out late last year, Americans are “fundamentally people who buy things”.

This type of trading heralds an identity crisis.