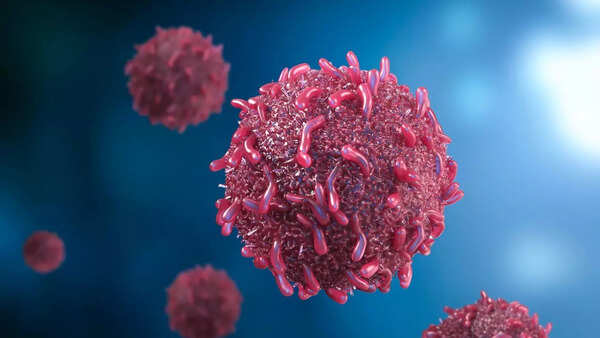

Cancer could be detected 3 years before symptoms appear with a simple blood test; new study reveals

A groundbreaking study by Johns Hopkins University researchers suggests a simple blood test could detect cancer up to three years before symptoms manifest. This innovation promises to revolutionize early diagnosis and significantly improve survival rates.

Published in Cancer Discovery, the study highlights the potential of early cancer detection. Identifying tumors in their initial stages allows for less aggressive treatments and better patient outcomes. Researcher Yuxuan Wang emphasizes that a three-year lead time allows for timely intervention, potentially transforming a life-threatening condition into a curable one.

The core of the research focuses on circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), genetic material shed by tumors into the bloodstream. Detecting these trace amounts of DNA early is challenging but crucial.

The Science Behind Early Cancer Detection

Scientists employ sophisticated algorithms to analyze blood samples for DNA pattern modifications indicative of tumors. This technique forms the basis of a Multi-Cancer Early Detection (MCED) test, specifically designed to identify cancer-specific genetic changes.

The research involved analyzing blood samples from 52 individuals, divided into two groups:

- 26 individuals diagnosed with cancer within six months of sample collection.

- 26 individuals who remained cancer-free.

The MCED test successfully flagged eight cancer cases, representing a 31% detection rate. Notably, this detection occurred before any formal diagnosis or visible symptoms.

Study Results: Detecting Cancer Earlier

Further analysis of older blood samples from participants revealed even more promising results. In six of the eight detected cases, samples taken 3.1 to 3.5 years prior to diagnosis were available. Remarkably, cancer signals were present in four of these samples.

Although ctDNA levels were significantly lower than the current test threshold, its presence suggests that tumors begin shedding DNA into the blood long before symptoms emerge. This highlights the need for increased sensitivity in current testing methods.

Dr. Bert Vogelstein, a senior cancer researcher, states that the study demonstrates the potential of MCED tests while also underscoring the sensitivity benchmarks that must be achieved for widespread success.

Next Steps After a Positive Blood Test

Despite the promising findings, translating these results into clinical practice requires further rigorous clinical trials to ensure reliability and safety. Regulatory approvals are also necessary before these tests can become standard medical practice. Additionally, protocols for appropriate clinical follow-up, including scans, biopsies, and preventive treatments, must be established following a positive test result.

This research signifies a potential paradigm shift in cancer diagnostics. Combined with ongoing advancements in targeted therapies, the future holds the promise of significantly enhanced survival rates and a revolutionary approach to cancer screening and treatment.

Newer articles

Older articles

-

Selena Gomez and Hailey Bieber UNFOLLOW each other amid Justin Bieber drama

Selena Gomez and Hailey Bieber UNFOLLOW each other amid Justin Bieber drama

-

Kajol reveals she watches horror films without sound: says it feels less scary

Kajol reveals she watches horror films without sound: says it feels less scary

-

When Shah Rukh Khan teased Aamir Khan over a cup of tea: "Kal bata dena yaar...."

When Shah Rukh Khan teased Aamir Khan over a cup of tea: "Kal bata dena yaar...."

-

‘Sitaare Zameen Par’ director RS Prasanna breaks silence on remake talk: 'The film will have the answers'

‘Sitaare Zameen Par’ director RS Prasanna breaks silence on remake talk: 'The film will have the answers'

-

Amitabh Bachchan calls working with son Abhishek Bachchan his 'greatest blessing'

Amitabh Bachchan calls working with son Abhishek Bachchan his 'greatest blessing'

-

Rath Yatra 2025: The legend of why Lord Jagannath’s idol was left incomplete

Rath Yatra 2025: The legend of why Lord Jagannath’s idol was left incomplete

-

Aamir Khan’s Sitaare Zameen Par picks up momentum on release day as last-hour bookings surge past 10,000 tickets

Aamir Khan’s Sitaare Zameen Par picks up momentum on release day as last-hour bookings surge past 10,000 tickets

-

Mona Singh reveals physical challenges behind her role in Aamir Khan's 'Laal Singh Chaddha': 'I had to completely transform my lifestyle'

Mona Singh reveals physical challenges behind her role in Aamir Khan's 'Laal Singh Chaddha': 'I had to completely transform my lifestyle'

-

Cheteshwar Pujara mocks Michael Vaughan's 4-0 prediction on Live TV, demands signature on failed post

Cheteshwar Pujara mocks Michael Vaughan's 4-0 prediction on Live TV, demands signature on failed post

-

Adnan Sami calls Pakistan an 'ex-lover' amid debate over his citizenship: 'Can’t see me moving on with India'

Adnan Sami calls Pakistan an 'ex-lover' amid debate over his citizenship: 'Can’t see me moving on with India'