FTAV’s further reading

Author: business

-

‘Beware a dollar confidence crisis’ — DB

Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Global Economy myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

There’s a lot going on at the moment, but the most interesting might be how the dollar has been absolutely tanked by yesterday’s tariff news.

The DXY dollar index has plunged 1.7 per cent today, taking it to its lowest since last autumn and extending its 2025 decline to almost 6 per cent.

In fact, the dollar is sliding against every single other major currency (oh, and the Swedish krona). Given how so many analysts long proclaimed that tariffs would be dollar positive, this is pretty notable.

© Bloomberg Why is this happening? The orthodox view was that tariffs were positive for the dollar because they are inflationary — and therefore keep rates high — and make the US currency scarcer.

However, the dollar’s recent weakness could be indicative that these factors are getting swamped by broad and growing international misgivings over the US. The madness behind the methodology of the recent tariffs certainly doesn’t encourage faith in the coherence of US policymaking. Many analysts are alarmed, but probably none more than Deutsche Bank.

“We are becoming increasingly concerned that the dollar is at risk of a broader confidence crisis,” George Saravelos, head of FX strategy at Deutsche Bank, wrote in a note he sent out to clients this morning.

We’ll quote at length here, given the importance of the topic. Deutsche Bank’s emphasis below:

We have been warning about the importance of the correlation breakdown between US risk assets and the dollar for a while — European losses on US assets are now exceeding those seen during the 2022-2023 crisis. The safe haven properties of the dollar are being eroded and this is imposing a significant cost on unhedged dollar holdings. Beyond that, developments since the start of the year make us worried about a broader undermining of confidence in the US economic outlook and the medium-term desirability of dollar allocations.

All of this risks a self-fulfilling unwind of extreme US asset overweights from countries that have exported capital to the US over the last decade. Most of the developed world belongs to this category. At the end of the day, the US has a large current account deficit, and the currency is reliant on capital inflows for stability. A drop in the dollar, a drop in US equities and a rise in term premium in US treasuries would be the strongest market signal that a process of US disinvestment is accelerating. A rise in term premia on US treasuries has not materialized yet, but it would be a very negative signal if it did.

Our overall message is that there is a risk that major shifts in capital flow allocations take over from currency fundamentals and that FX moves become disorderly. We would caution that if the dollar decline accelerates, it would be a highly unwelcome development for global central banks. The last thing the ECB wants is an externally imposed disinflationary shock from a loss in dollar confidence and a sharp appreciation in the euro on top of tariffs. Expect pushback. We are in the midst of dramatic regime change in markets.

-

Where the Bank of England’s QE programme went wrong

Christopher Mahon is head of Dynamic Real Return in Multi-Asset Investing at Columbia Threadneedle Investments.

In February, the Bank of England updated its estimates for the lifetime losses of the asset purchase facility, the vehicle through which it conducts quantitative easing.

Its prediction for APF losses had crept up: from £95bn in September, to £115bn at the year end. The scale of these figures — and the change, in a matter of months — dwarf the £14bn of savings chancellor Rachel Reeves announced in her spring statement.

Now, some might argue that comparing a lifetime figure to an annual budget is unfair. And the purported benefits of QE — supporting the economy during some of its darkest days — risk being overlooked if the focus lands too much on the bottom line. But these are big, unignorable numbers — so how should we think about the financial out-turns of the BoE’s QE programme?

Recap: How QE works

To recap the mechanics of these losses: under QE, the BoE borrowed cash to buy government bonds (and the bonds of select companies) to support the economy. Financially speaking, this appeared to work well while cash rates were zero and locking in a 1 per cent yield on a 30-year gilt looked attractive.

But fast forward to today, with cash rates at 4-5 per cent or higher, and the same 1 per cent yield locked in for 30 years isn’t quite such a good deal. In fact, it is immensely costly, as a result of the “negative carry” on those low-yielding bonds.

How the BoE losses compare

One way to think about these losses is to compare the BoE against other central banks. Each supported their economies more or less successfully through QE, so we can look at which central bank provided this help for the lowest cost, in the most efficient manner.

However, with each central bank using its own accounting methods — with varying degrees of transparency — this is no easy task.

What we do know is what type of bonds each central bank bought, the dates of the purchases and how the bonds have performed since. Combined with certain other approximations, we can create rough mark-to-market estimates of the profit and loss of each of the central bank’s government bond holdings.

It won’t be perfect, but this approach allows for a rough and ready like-for-like comparison. On this basis, our broad estimates of the cumulative losses since QE began are shown below:

The picture is much worse for the Bank of England than its peers, with losses nearly four times the Fed’s. Why is this?

Well, here’s a handy cheat sheet of the key choices the BoE made compared to the Fed:

The first two rows are the most significant. The ~4x worse losses on the BoE’s government bond holdings boil down to the BoE owning roughly twice as many gilts, and them being twice as rate sensitive as the Fed’s treasuries:

Maturity risk vs maturity mismatch

A big chunk of the losses come from the long maturity bonds that were more of a focus for the BoE. As an example, during QE in May 2020 the BoE bought a series of 2061 gilts at a price of £101. Under QT it has been selling the same securities at prices as low as £28, a loss of 73 per cent.

Arguably, these longer-dated maturities did not need to be bought at all. As an example: UK household borrowings are far shorter than in the US (think 5-year mortgages vs 30-year in the US). The transmission mechanism to the wider economy from buying a 30 or 50-year gilt was always fairly limited.

With the Fed choosing to focus QE only on certain parts of the curve, there was a good reason for the BoE to consider doing similarly, tailoring their focus to suit local conditions, rather than buying quasi-passively all the way along the curve.

The role of active QT

It is too late to salvage most of these losses. But, when it comes to reversing QE though quantitative tightening, the BoE again finds itself on its own. Only the BoE is actively selling their holdings into the market — no other major central bank is pursuing QT in this way. Others are simply opting for the passive method of allowing their bonds to mature without replacement. The Fed is still partially reinvesting coupons.

The BoE argues this difference makes little impact. Others take a different view.

Research published by NBER last year highlighted how the BoE’s QT programme has had a negative impact on long-term bond yields4.

Researchers found a ~70 bps impact on long term gilt yields, against a 15-20bps impact from QT in the US — with a good portion of the difference being driven by active QT:

Certainly, the underperformance in gilts versus treasuries since QT began is noteworthy. Our own view is a combination of active QT, a faster pace of QT, and no coupon reinvestment has been weighing on gilts and perhaps adding about 30-40bps to yields versus comparable markets:

How to reconcile the Bank’s benign view against these more pessimistic assessments? The BoE’s own research tends to focus on the lack of evidence of market dislocations. But prices can be pushed down by a large seller without disorder and without liquidity worsening.

The incurious MPC

Perhaps surprisingly given the scale of the losses — and unlike decisions on interest rates — decisions about QE typically see unanimous votes by the MPC. Few public differences are aired or orthodoxies challenged. There is little reflection on the strengths or weaknesses in the UK’s approach. And there is no real acknowledgment of the alternative configurations that were — and still are — possible.

The BoE has avoided allowing consideration of profits or losses to drive changes in policy. Deputy governor Sir Dave Ramsden stated: “The MPC does not take into account financial risk or profit when taking monetary policy decisions, including about the gilt portfolio”.

Well, maybe it should. After all, taxpayers have to fund these losses. And if other central banks can do it cheaper, maybe there are lessons to be learnt.

Even at this late hour, if we are right about active QT exacerbating the supply demand imbalance in the gilt market, cancelling the extra sales from active QT and returning to central bank norms could be worth an ongoing £1bn per year saving to the Treasury in lower interest costs.

Please, Governor, can we have no more?

-

you won’t believe how they came up with the numbers

Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Americans were told reciprocal tariffs would be simple. “Reciprocal, that means they do it to us, and we do it to them,” said President Donald Trump on Wednesday. “Very simple, can’t get any simpler than that.”

Then the full list of countries’ tariffs came out, and it was . . . not simple. At least not in the “easily understood” meaning of the word.

The rates were supposedly based on the US Trade Representative’s calculations of “tariffs imposed against US products”. But they didn’t come from any obvious rates that were actually imposed, as Paul Krugman pointed out.

So how did they come up with these numbers in the first place? Turns out that there is some method to the madness! It’s just a nonsensical method, if it’s what we think.

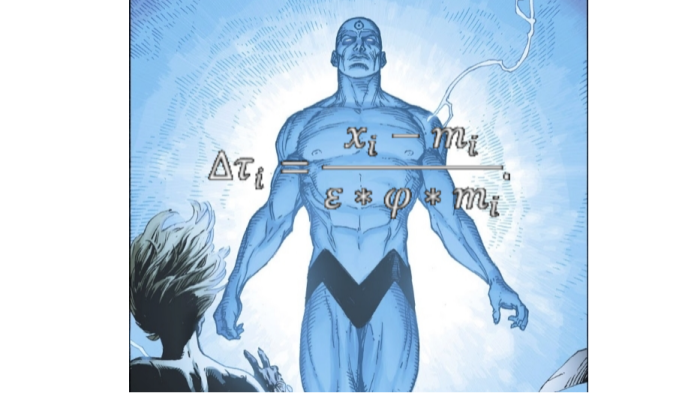

Here’s what the White House and its crack team of trade investigators seems to have done: Take the US’s goods trade deficit with any particular country, and divide it by the total amount of goods imported from that country. Cut that percentage in half, and there’s the US’s “reciprocal” tariff rate.

We can confirm this fits* the numbers for the first 24 countries listed, which we checked by hand because we could hardly believe it and also because we refuse to use AI for anything. Kudos to @orthonormalist and James Surowiecki, who both put it together, more or less.

Let’s look at Bangladesh as an example. The US imported $8.4bn of goods from Bangladesh in 2024, giving it a $6.2bn trade deficit with the country. 6.2 divided by 8.4 is 0.738.

And what do you know? The White House says that the country has “charged” 74 per cent “tariffs” against the US, “including currency manipulation and trade barriers”.

Trying to assign a macro narrative to this calculation method is enough to make even a hack strategist’s blood run cold.

Is the US . . . implying that all trade deficits are the result of unfair practices or currency manipulation? What about comparative advantage? David Ricardo is surely spinning in his grave. What about bananas? They don’t grow in the US! Is it worrying that some posters got this method when they asked major LLMs about easy ways to impose tariffs? This is bananas.

Unnamed officials doubled down on the methodology to the New York Post:

The specific “reciprocal” tariff rate was roughly half of the current trade imbalance because “the president is lenient and he wants to be kind to the world,” a Trump aide told reporters.

“The numbers [for tariffs by country] have been calculated by the Council of Economic Advisers … based on the concept that the trade deficit that we have with any given country is the sum of all trade practices, the sum of all cheating,” a White House official said, calling it “the most fair thing in the world.”

UPDATE: You can also find what the US Trade Representative says about reciprocal tariff calculations here. Long story short: The White House wants to shrink the US’s trade deficit, it seems. This does not bode well for fans of coffee or bananas or other produce that doesn’t grow in the US.

Risk markets hated the news, predictably. S&P 500 futures were down 2.7 per cent around 10pm in New York. Nasdaq futures were down 3.4 per cent. And here’s

betacoinEthereum:Anyway, we’ll see how long it lasts, we guess? There has been some debate about what legal authority the White House can claim to impose tariffs, and officials seem to have picked all of them that could apply in the latest Executive Order: The International Emergency Economic Powers Act; the National Emergencies Act; and sections 604 and 301 of the Trade Act of 1974.

When it comes to the total impact, lots of bizarre numbers have been thrown around. But the Budget Lab at Yale did a nice analysis, and found Wednesday’s tariffs boosted the US’s effective rate another 11.5 percentage points to 22.5 per cent, the highest level since 1909.

If trade wars are indeed class wars, this was a pretty noisy and chaotic shot across the bow.

*The only discrepancies we found in that group were Sri Lanka, which had 87 per cent instead of 88 per cent, and what could be some messy rounding. The next 24 countries were a little messier, but could still more or less be explained by sloppy rounding, with the exception of Jordan, Tunisia and Kazakhstan, which were all off by a percentage point or two.

Update: Toby’s cross-referenced the numbers and produced “the stupidest chart you’ll see today”. Bon appétit!

-

If times feel uncertain, it’s because they are

Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what the 2024 US election means for Washington and the world

Compared with the past, the present always feels uncertain. To the attentive analyst — or even human — risks abound.

Today certainly feels pretty risky and uncertain. But how does it really measure up?

Back in 2022, a couple of Federal Reserve economists — Dario Caldara and Matteo Iacoviello — published a paper in the American Economic Review that attempted to quantify geopolitical uncertainty.

They built upon an historical database containing tens of millions of newspaper articles, and scanned a further 30,000 articles in a month from English-language newspapers (including the Financial Times). They then assessed the frequency of newspaper articles discussing adverse geopolitical events as a percentage of total articles.

Having released replication packages to allow others to reproduce their results, and kept their website updated with close-to-current data, the Caldara/Iacoviello model has become fairly widely used. Here’s how it looks:

Their model has done a pretty good job in spiking at the times you’d expect a geopolitical risk index to spike. And although its latest readings are uncomfortably high, it isn’t in event-shock territory. So risky, but not super-risky.

But when we move away from broad measures of geopolitical risk and towards measures of policy uncertainty the picture darkens.

In 2016, three academics — Scott Baker, Nicholas Bloom, and Steven Davis — put together an index of US economic policy uncertainty based not only on newspaper articles, but also upon the number of federal tax code provisions set to expire, and a measure of disagreement among economic forecasters. Furthermore, they built topic-specific subindices of policy uncertainty.

How do things look at the headline level?

Yikes!

Okay, so a big input into this index is an historically normalised news-based component, and we’ve included this component to show how much uncertainty is being transmitted through the American media. But still, we’re approaching the kinds of uncertainty readings seen only during a global pandemic that included the economy being pretty much shut down.

What about uncertainty across different categories of economic policy? Here we move back again to news-only indices.

We’ve popped the relevant Baker/Bloom/Davis model data into a chart below — use the filter to toggle between uncertainty indices as they relate to Monetary Policy, Fiscal Policy, Health Care policy, Entitlement programs, etc:

While there isn’t an unprecedented level of uncertainty in many of these areas (trade policy being a notable exception), uncertainty readings are close to extremes in quite a large number of policy areas.

Alphaville highlighted the global version of this uncertainty index back in February, and how it had become disconnected to market measures of uncertainty used in options pricing. It seems that markets have since caught up.

Why does this matter? Businesses are basically planning machines. If they lack confidence in the future they’re less likely to invest or hire people. Not great.

Now, we know what you’re thinking. How would all these categorical uncertainty index data look in an animated interactive radar chart that plotted values for each category of economic uncertainty in the form of its percentile reading relative to its own history. Don’t worry — we’ve got your back:

As FT trade guru Alan Beattie has reminded us all for the last two months, when it comes to US policy, Nobody Knows Anything.

-

Khám Phá W88 – Nền Tảng Giải Trí Đỉnh Cao Cho Người Chơi

W88 là một trong những nền tảng giải trí trực tuyến hàng đầu hiện nay, nơi người chơi có thể tận hưởng nhiều trò chơi thú vị và hấp dẫn. Với sự phát triển không ngừng của công nghệ, W88 đã trở thành điểm đến lý tưởng cho những ai yêu thích cá cược, casino và thể thao.

Sự Phát Triển Của W88 Trong Ngành Giải Trí Trực Tuyến

Sự Phát Triển Của W88 Trong Ngành Giải Trí Trực Tuyến

Trước khi đi sâu vào các khía cạnh khác nhau của W88, điều quan trọng là hiểu rõ về sự phát triển của nền tảng này trong ngành giải trí trực tuyến. W88 không chỉ đơn thuần là một trang web cá cược mà còn là biểu tượng cho một xu hướng mới trong lĩnh vực giải trí số.

Lịch sử hình thành và phát triển

Kể từ khi ra mắt, W88 đã không ngừng mở rộng và cải tiến dịch vụ của mình để đáp ứng nhu cầu ngày càng cao của người chơi. Thương hiệu này đã xây dựng được uy tín vững vàng và thu hút hàng triệu người dùng trên toàn thế giới.

Được thành lập dựa trên mục tiêu mang lại trải nghiệm chơi game tốt nhất, W88 đã nhanh chóng phát triển với nhiều sản phẩm đa dạng, từ cá cược thể thao, casino trực tuyến đến slot game.

Đặc điểm nổi bật của W88

W88 luôn chú trọng đến việc nâng cao trải nghiệm người dùng thông qua giao diện thân thiện và dễ sử dụng. Nền tảng này cung cấp nhiều tùy chọn thanh toán linh hoạt, đảm bảo người chơi có thể thực hiện giao dịch một cách thuận lợi nhất.

Bên cạnh đó, W88 cũng thường xuyên cập nhật và bổ sung các trò chơi mới, giúp người chơi luôn có những trải nghiệm mới mẻ và thú vị.

Tầm ảnh hưởng toàn cầu

Với sự phát triển mạnh mẽ của công nghệ di động, W88 đã nhanh chóng bắt kịp xu hướng này bằng cách tối ưu hóa trang web cho thiết bị di động. Điều này giúp người chơi có thể tham gia cá cược mọi lúc mọi nơi chỉ với một chiếc điện thoại thông minh.

Ngoài ra, W88 còn có hệ thống hỗ trợ khách hàng 24/7, giúp người chơi giải quyết nhanh chóng các vấn đề phát sinh trong quá trình chơi.

Các Trò Chơi Đặc Sắc Tại W88

Các Trò Chơi Đặc Sắc Tại W88

Một trong những yếu tố quyết định sự thành công của W88 chính là danh sách trò chơi phong phú và đa dạng. W88 cung cấp một loạt các lựa chọn cho người chơi, từ cá cược thể thao đến các trò chơi casino hấp dẫn.

Cá cược thể thao

Cá cược thể thao tại W88 là một trong những lĩnh vực thu hút đông đảo người chơi nhất. Người dùng có thể đặt cược vào nhiều môn thể thao khác nhau, từ bóng đá, bóng rổ đến quần vợt và đua xe.

Nền tảng này còn cung cấp những phân tích chi tiết về các trận đấu, giúp người chơi đưa ra quyết định thông minh hơn. Bằng cách cập nhật liên tục thông tin và thống kê, W88 tạo điều kiện cho người chơi có cái nhìn tổng quan hơn về các đội bóng và vận động viên.

Casino trực tuyến

Casino trực tuyến là một phần không thể thiếu trong W88. Tại đây, người chơi sẽ được trải nghiệm những trò chơi như blackjack, roulette, baccarat, và nhiều trò chơi khác.

Điều đặc biệt là W88 cung cấp trải nghiệm chơi casino trực tiếp, nơi người chơi có thể tương tác với dealer thực tế thông qua video streaming. Điều này giúp tạo cảm giác chân thật như đang ở một casino lớn.

Slot game

Không thể không nhắc đến slot game tại W88, nơi mà người chơi có thể thử vận may với hàng trăm máy đánh bạc khác nhau. Những slot game này thường đi kèm với các chủ đề hấp dẫn và tính năng thưởng phong phú.

Thêm vào đó, W88 cung cấp các giải đấu slot đầy hấp dẫn, nơi người chơi có cơ hội nhận giải thưởng lớn chỉ với một khoản tiền cược nhỏ.

Hệ Thống Khuyến Mãi Và Ưu Đãi Tại W88

W88 không chỉ thu hút người chơi bằng các trò chơi chất lượng mà còn bởi những chương trình khuyến mãi hấp dẫn. Những ưu đãi này không chỉ giúp người chơi có thêm cơ hội kiếm tiền mà còn tăng cường trải nghiệm chơi game.

Khuyến mãi đăng ký

Người chơi mới khi đăng ký tài khoản tại W88 thường được hưởng các gói khuyến mãi hấp dẫn, bao gồm tiền thưởng chào mừng và nhiều phần quà khác. Điều này không chỉ tạo động lực cho người chơi mới mà còn giúp họ có thêm vốn để bắt đầu hành trình cá cược.

Khuyến mãi cho người chơi cũ

Đối với người chơi cũ, W88 cũng không bỏ quên với nhiều chương trình khuyến mãi định kỳ. Những ưu đãi này thường bao gồm hoàn tiền, giảm giá cho các trò chơi cụ thể hoặc các giải đấu với giải thưởng hấp dẫn.

Ngoài ra, W88 cũng có chương trình VIP dành cho những người chơi thường xuyên, giúp họ nhận được những quyền lợi đặc biệt và ưu đãi riêng.

Chương trình cashback và hoàn tiền

Một trong những điểm hấp dẫn của W88 là chương trình cashback, giúp người chơi có thể lấy lại một phần tiền thua cược. Điều này giúp giảm thiểu rủi ro cho người chơi và tạo điều kiện để họ có thể tiếp tục tham gia cá cược mà không phải lo lắng nhiều.

An Toàn Và Bảo Mật Khi Chơi Tại W88

An Toàn Và Bảo Mật Khi Chơi Tại W88

An toàn và bảo mật là vấn đề cực kỳ quan trọng trong lĩnh vực cá cược trực tuyến. W88 luôn chú trọng đến việc bảo vệ thông tin cá nhân và tài khoản của người chơi.

Công nghệ mã hóa tiên tiến

W88 áp dụng công nghệ mã hóa SSL tiên tiến để bảo vệ dữ liệu cá nhân của người chơi. Điều này đảm bảo rằng mọi thông tin giao dịch đều được bảo mật và an toàn trước sự truy cập trái phép.

Ngoài ra, tất cả các giao dịch tài chính đều được thực hiện qua các cổng thanh toán uy tín, giúp người chơi yên tâm hơn khi gửi và rút tiền.

Chính sách bảo mật thông tin

W88 cam kết không chia sẻ thông tin cá nhân của người chơi với bên thứ ba mà không có sự đồng ý của họ. Chính sách bảo mật này được thực hiện nghiêm túc, đảm bảo rằng quyền lợi của người chơi luôn được đặt lên hàng đầu.

Hỗ trợ khách hàng chuyên nghiệp

W88 có đội ngũ hỗ trợ khách hàng chuyên nghiệp và tận tình, sẵn sàng giải đáp mọi thắc mắc của người chơi 24/7. Nếu gặp bất kỳ vấn đề gì, người chơi có thể nhanh chóng liên hệ để được tư vấn và hỗ trợ kịp thời.

Kết luận

W88 không chỉ là một nền tảng cá cược trực tuyến thông thường mà còn là một trải nghiệm giải trí độc đáo và tuyệt vời cho mọi người chơi. Với danh sách các trò chơi đa dạng, chương trình khuyến mãi hấp dẫn cùng với sự đảm bảo về an toàn và bảo mật, W88 thực sự xứng đáng là lựa chọn hàng đầu cho những ai yêu thích thể loại này

-

The ONS vs the Xbox

The UK’s February inflation stats were a pleasant surprise for a couple of reasons.

Firstly, the year-on-year growth rate fell to 2.8 per cent, closer to target than economists had forecast. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, the Office for National Statistics updated its price quote data sets with a new glossary (direct download link) and data structure.

We’ve already spent a lot of time dwelling on the price quotes tables, which all the prices ONS agents observed for certain items in the inflationary ‘basket’. So why not spend some more?

Until February 2020, the ONS tracked an item called “Computer game top 20 chart”. At that point, it was into three different categories, imaginatively named Computer Game 1, Computer Game 2 and Computer Game 3.

An ONS spokesperson told us:

Splitting into three categories allows us to obtain more price quotes on what is one of the most volatile areas of the consumer basket. This improves the overall estimate, reduces volatility and aids users to more easily interpret these data.

According to the 2019 CPI manual, computer games — like certain other items, such as books and DVDs — are subject to special rules when it comes to price collection. For bestselling books, agents would get three price quotes, and computer games worked similarly.

Here’s how the price monitoring theoretically works: first up, a computer game is selected from a retailer’s bestsellers list. The price of that title is then tracked month-by-month based on shelf price. If the game falls out of the bestsellers list, an alternative game is collected.

So, say a new Call of Duty title is selected. An agent observes its price at £44.99 in a given shop. Eleven months later, the same game is still in the top 20, but is now £24.99. The next month, the Call of Duty title has dropped out of the top 20. The agent now picks a different game, and observes its price instead.

From an “inflation data should capture inflation” perspective, the ideal way for this to work is that perhaps:

1) The first game doesn’t drop in price as rapidly as in that example, and:

2) The game they replace it with is just a newer Call of Duty game.In that way, you’re hopefully, roughly, measuring the rate of inflation in the price of an AAA game. And, because of smooth year-on-year replacement, there aren’t sudden jerky movements in the year-on-year growth rate (even if the actual cost resets to its high point each year).

There are several problems with this approach:

1) Month-on-month inflation with regards to this item reflects the price decay of a particular game relative to its price at launch, rather than offering good indication of the overall change in the price of video games as a whole.

2) Say the first Call of Duty game stays in the top 20 for seventeen months, and then drops out. If it is then replaced with a newer title that came out in the meantime, you would see lumpy shifts in the year-on-year rate.

3) Different games may experience price decay at significantly different rates — particularly ones like the Fifa titles, which are bought as much for the latest kits and player data as for actual game features.Per the ONS’s detailed guidance, which we recently acquired, here’s what agents are being told to price:

The redactions are frustrating, and reflect the ONS’s general refusal to name specific brands and products. But permit us to go a little bit through the looking glass, and to reobserve the original file we based that data upon:

Those redacted sections, as you can clearly see…

us rn …are of different lengths, because, duh, they’re telling agents to look for different things.

What those bars hide is indicated by the guidance: agents are told to “[c]heck correct platform”, because they’re being asked to observe games for three different platforms.

And, thanks to the new data structure mentioned above, it’s a bit clearer what those platforms are. In the new version of the price quotes, the item description (eg “Computer game 1”) is joined with a “consumption category” description:

So, we can surmise agents are asked to observe three games in the physical retailers they visit: one from the Nintendo Switch top 20, and one each from the PlayStation and Xbox top 20s.

And while the guidance suggests agents “[t]ry to price different titles for the 3 games” — an attempt to diversify the pool — it implies one could (doing their job badly) observe Fifa for all three consoles.

It might make sense for there to be some kind of central guidance in place, saying eg: “We’re currently trying to observe Call of Duty for Xbox, Fifa for PlayStation and Animal Crossing for Nintendo Switch”, but because bestseller charts vary by shop, so do the game choices. An ONS spokesperson told us:

The replacement is at the discretion of the collector and the guidance is to select a replacement that is representative of the stock in the shop. They will consider the stock on the shelves, and potentially use the type of game or the type of customer it’s aimed at to select a similar replacement.

This means an agent in, say, Reading could track their Computer game 1 (Nintendo) in Currys as Fifa, while another observes Super Mario Party Jamboree in Currys Skegness. In a classic case of smallcagedmammalness, the average price could then end up reflecting this arbitrary compositional mix.

In terms of how inflation is calculated (based on “elementary aggregates” derived from the prices collected from one stratum, typically delineated by region and shop type), these things shouldn’t matter much as long as the Reading agent keeps checking Fifa during their Currys run, and the Skegness one keeps checking Super Mario Party Jamboree during theirs. Which, as we’ve already seen, they won’t.

Time for a chart:

Xbox, u OK hun? The apparent seismic drop in the price of a game for Microsoft’s console largely drove a decline in the “Games, toys & hobbies” subcomponent of CPI during February, according to Robert Wood from Pantheon Macroeconomics. The PlayStation game has also had some pretty wild moments, particularly in early 2021.

Wood told us:

The CPI is a bit like a sausage; the more you think about what goes into it the less appetising it looks. Computer games are one of many data collection problems that mean the CPI is more volatile than it should be, and in some months probably does not fully reflect the reality on the ground.

Notoriously volatile computer game prices drive unnecessarily erratic movements in inflation from month to month. By collecting the prices of only a limited number of computer games, and seemingly substituting game titles with hugely different prices when a game becomes unavailable, the ONS delivers wildly volatile price readings that almost certainly fail to reflect the underlying reality of game prices but move headline CPI.

In fairness to the statisticians, they are trying to improve the use of industry scanner data in the CPI, which will massively increase sample sizes. That is complex work. But it’s still a huge failing that the ONS currently has such a limited volatile sample of computer games and some other items.

What, fundamentally, is going wrong here? As mentioned previously, the model of vibes-based title selection and sporadic replacement seems bound to create volatility, but this volatility seems alarmingly chronic. An ONS spokesperson told us:

Computer game prices are particularly volatile and do show wide price range fluctuations over both long and short-term time periods. The degree of volatility across the three games would depend on the speed with which products enter and leave the charts, and the price distribution of products within that particular item.

Nintendo games are, apparently, a relative beacon of stability. The ONS’s refusal to share specific information on item choices means we can only speculate why, but there’s a pretty obvious hypothesis: unlike its more powerful console cousins, with their constant game edition updates, the Nintendo Switch has a pool of popular titles that have been stable for the whole period captured here. For example, this could just be an index mainly of the price of Mario Kart 8, which launched at about £45 in 2017, and still retails at about £38.

It doesn’t seem that simple — though it’s hard to tell why. One possible clue is in the sheer number of agents who weren’t able to observe a price for the game they were seeking, and instead gave it an “M” code for “missing”. Here are those figures for February:

Yuck. So whatever it was they were looking for, fewer than a third of the ONS’s agents managed to find it.

But something more weird is happening here. Let’s repeat that exercise, but divide things up into simply accepted/rejected (technically it’s a measure of how many attempted prize observations resulted in a success/failure) and take in the long view since 2019 (when the general top 20 item was on its last legs):

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

This might be a product of some underlying change in the basket, or possibly a conscious drive to make more observations of these items. We asked the ONS for more details, and a spokesperson told us:

The collection in February was the same as January with some of the shops from which we attempt to collect price quotes not stocking computer games. It was not a case of quotes being “rejected”. The difference between January and February was that the records for these price quotes were not included in the microdataset in January but were included in February. We have introduced new systems from February and, to improve transparency, they pass this additional data into the published file. Clearly these records containing no quotes are not used in producing the indices.

Yay for transparency! Moving on…

What were they observing? As might be expected at this point, it seems inconsistent:

It’s not quite RROD version two, but something’s definitely going wrong with the Xbox — look at that spread, and the heavy reliance on comparable (plus symbol) rather than identical (circle symbol) item observations. Effectively, there were only two observations — out of 98 attempts — where an ONS’s agent found the product they were looking for. No wonder the series is being weird.

Let’s go shop-by-shop, focusing on Xbox. We know from previous coverage that once you filter down by region, shop code and shop type you can create a continuous price series for a shop.

Intuitively you’d expect the price series for a set game at a set shop to be fairly smooth, with occasional adjustments. What we absolutely don’t expect to see are a load of wild and wiggly lines:

Womp.