Funny how stuff comes together sometimes.

Last month, mainFT’s Valentina Romei and our very own Robin covered how a January surge in US gold imports by traders trying to get ahead of tariffs had temporarily broken the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow model, leading it to indicate a looming recession. The culprit behind the leap in “finished metal shape” (aka gold bar) imports was Switzerland.

And if you’re a Swiss cheese exporter with a large US clientele, that could end up mattering a lot, depending on the future whims of the White House.

The reason is simple — again, in a stupid kind of way. We’ve dwelled a lot upon how inane the Trump Administration’s “discounted”, “reciprocal” tariff calculation is.

If you’ve somehow missed it, it’s broadly (with some exceptions, including a blanket 20 per cent levy on EU goods): take America’s 2024 trade balance with a country, divide it by the amount the US imported from that country, divide the result by two, and make that the tariff percentage. If the percentage is below 10, make it 10. Sorry to the UK.

It’s a crude mechanism, and one that produces particularly wild results for smaller economies that often simply sell the US things the US can’t make or grow itself.

But it’s easy to get caught in the stupefying simplicity of the calculation, and ignore the stupefying simplicity of the data pool. Justifying the tariffs, the USTR release says:

The failure of trade deficits to balance has many causes, with tariff and non-tariff economic fundamentals as major contributors. Regulatory barriers to American products, environmental reviews, differences in consumption tax rates, compliance hurdles and costs, currency manipulation and undervaluation all serve to deter American goods and keep trade balances distorted. As a result, U.S. consumer demand has been siphoned out of the U.S. economy into the global economy, leading to the closure of more than 90,000 American factories since 1997, and a decline in our manufacturing workforce of more than 6.6 million jobs, more than a third from its peak.

So how better to assess that epochal, multi-decade economic shift than by extrapolating an entire policy from only 2024 data?

Back to Switzerland. Exports of goods deemed Swiss to the US face a reciprocal tariff of 31 per cent — markedly higher than that flat 20-per-cent EU rate — reflecting $64bn of Swiss exports to the US and a trade surplus of $39bn against the Americans in 2024.

Now, the GDPNow-distorting influx of gold fell within 2025, but the US also saw less extreme “finished metal shapes” jumps last year that lined up with rises in imports from Switzerland. In short, the overall Swiss 2024 numbers also seem to be unusually swollen by the yellow stuff.

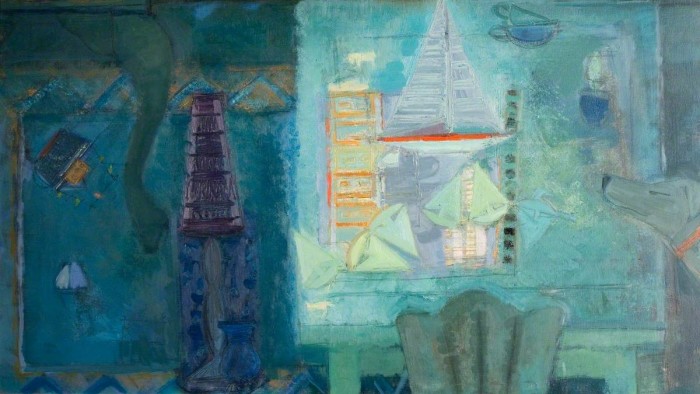

So how different might Wednesday’s tariff announcement have been if “Liberation Day” had been this time last year, based on 2023’s figures, or in another recent-ish year? Well, quite a lot:

It’s a tough break for Swiss cheesemakers and clockmakers, who now face a bigger tariff barrier than they might have got in 2024 or 2023. But could things get worse?

Let’s imagine “Liberation Day” becomes an annual occurrence — a federal stock-market holiday, even! — and on April 2, journalists gather in the Oval Office as the President presents updated tariffs based on the same formula. This would probably create all kinds of odd situations around countries trying to game their trade stats, but for now let’s hand-wave that away.

Over enough time, this could mean the long-term average tariffs paid are “fairer”, insofar as the (crude, unfair) tariffs would at least not be biased by any potential oddities of a single year, 2024.

Of course, rates could still end up biased by a series of other potential oddities from other individual years. That potential volatility would force exporters to the US to plan for a future in which the price of their goods fluctuates wildly each year based on their country’s annual trade balance. Not great for planning.

But there is no clear plan for “Liberation Day” to be an annual occurrence, of course. These tariffs are supposedly going to be the baseline for the rest of the Trump Administration; or until President Trump changes his mind; or possibly forever, depending on how confident you feel about the strength of US institutions. In other words, 2024’s trade data might end up mattering for a long time. Who might then appear be victim of timing, and who might have just got lucky?

Well, here are all the countries for whom FT Alphaville could get enough sequential data to roughly answer that question. Relatively bigger 2024 column compare with previous years = more hard-done-by. Relatively smaller = a good year to be tariffed on:

(Note that in this and the subsequent diagrams we’ve shown EU countries as disaggregated, ie they get a variable 2020–23 implied rate and only receive the blanket 20 per treatment for 2024.)

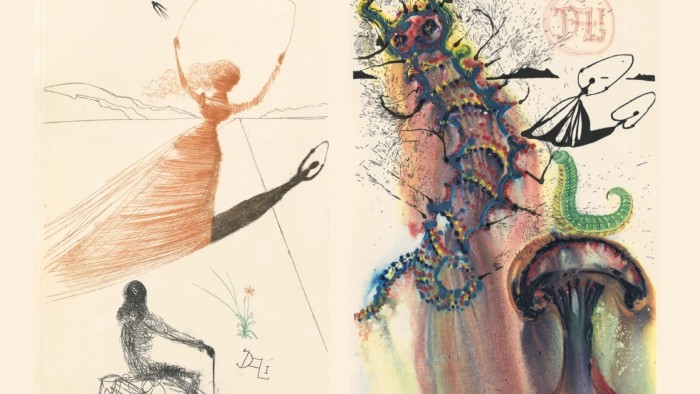

Sequencing them by the spread between 2023’s implied rate and 2024’s actual rate, things look tough for Vanuatu and Laos (and we’re left wondering what happened in Comoros last year):

We will concede that the Y-axis labels above are unforgivably small, but we refuse to change that because 2023 is of course equally flawed as a single year to look at.

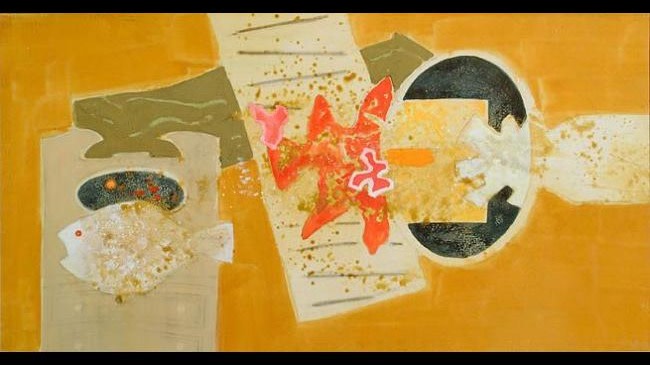

A mildly better way to assess fairness is to compare the applied tariffs to some kind of average. So now that we understand the system, let’s compare the announced rates with an theoretical average over five years (even though that will capture some pandemic-era jankiness):

Vanuatu . . . ouch. Assuming its trade relationship normalises to recent trends this year, Vanuatuan exporters should really hope Liberation Day does become a regular thing.

Swiss cheesemakers may feel differently. As a reminder, here’s how the US/Swiss trade relationship shifted in January:

Managing roughly half an ordinary year’s worth of exports to the US in a single month means — if Liberation Day does return — that Switzerland could be on track for a horrible tariff recalculation.

If so — and unless there’s a monumental reversal over the rest of this year — then 2 April 2026 would be a bad day in the Swiss dairy.

Further reading:

— O dirang, Donald? (FTAV)

— Reciprocal tariffs: You won’t believe how they came up with the numbers (FTAV)

— The stupidest chart you’ll see today (FTAV)

— Academic citation malpractice, reciprocal tariffs edition (FTAV)